Looking Back on 20 Years of Writing, Part 9: Dr. Coffee's Pill (2004)

I really don't want to write this one. There. I've said it. Now I have to stop procrastinating and get it done.

Don't get the wrong idea! I love "Dr. Coffee's Pill." It's one of my favorites, and I'm very proud of it. I just re-read it, in fact, in preparation for writing this blog, and I didn't cringe once. Well, maybe once, when I saw a "he" that might have been better clarified in the narration, but the dialogue made it clear whom I was referring to, so ... I am now both overthinking and procrastinating.

Here's the thing. "Dr. Coffee's Pill" is a short story about the relationship between art and pain, and, for me, it is a story that comes from a place of deep personal pain; a pain that might have killed me once, as I see it.

So ... Let's talk about "Generation X." We weren't given that label for following the non-existent Generation W, no. We were given that name by the Baby Boomers more in line with the term "Brand X." The lesser ones. We weren't like them, and therefore, we were basically deemed defective by the mainstream media of the time. I don't want to overdo it with generalizations here. There are billions of humans on the earth, and more exceptions to every generalization than I am willing to try my hand at counting. That being said, yes, I am using generalizations to make my point, because the generalizations match my experience, and stopping to point out every exceptional member of each generation whom I personally know would be tedious. Suffice it to say, I acknowledge these individuals, and this is not a story about them.

Looking back at my life, I have noticed that most Baby Boomers I knew growing up were extremely good with children, aside from beating the hell out of them. They doted on their children, as long as they could. Gen X was the last generation to have the luxury of a stay-at-home parent, until we became the first generation of what the media dubbed "latch-key kids." The divorce rate skyrocketed with the Baby Boomers, and we wound up with no parent having the luxury of time. Everyone had to have a job. The media dubbed our homes "broken." Gen X got home to an empty house after school. We looked to the television for guidance, as we microwaved our own meals and waited for whichever tired parent we lived with to get home. I'm not saying this to elicit pity; I'm simply pointing out that there was a dramatic change in the average family dynamic, and it threw everyone for a loop. I never bemoaned being a "latch-key kid," at the time. The media did that for me. I was fine with it. I learned to enjoy my independence in the hours when no adults were around to advise me, to tell me yes or no. Still, It was when Gen X hit adolescence, specifically those of us born in the '70s and early '80s, that the Baby Boomers generally stopped liking us so much. Suddenly, we weren't the obedient and adoring children we had always been. We were angsty teenagers who listened to "immoral" music and dressed like slobs. We didn't jump for joy to greet them when they got home anymore. We were too busy being developmentally normal adolescents and distancing ourselves from parental authority as well as we could. Our parents didn't have the energy or the patience for it, nor were they very inclined to stop and evaluate what was happening, or whether or not it was to be expected. All they saw were behavioral changes they didn't have time to nurture us through.

A lot of us were embittered by their sudden absence in our lives, as we made an effort to spread our wings. And a lot of our parents were embittered by the loss of their innocent children who were now obnoxious teenagers, too big to successfully beat without us realizing we could hit back. As a result, in the late 1980s, there was a trend of teenagers being needlessly tossed into mental hospitals by their parents, who simply didn't know what to do with teenagers. In their minds, teenagers, "Generation X," were the worst, most ungrateful, and mentally deranged people in the world. If they couldn't subdue us with Ritalin, there was nothing else for it. We had to be institutionalized until we learned to either revert to being obedient children or grow instantly into fully functional and responsible adults. There was no time for any in-between phase.

The message was simple. Conform, or vanish.

I was no exception to this trend, and it's another part of my story I don't like to talk about.

In 1988, my mother and father had just divorced. I don't want to get into the private details too much, for the sake of respecting everyone involved. I will say, it was an ugly divorce, and, in that, it wasn't very exceptional. I was luckier than most kids my age, in that my father remained in my life. He left our home, but he didn't leave us. It probably would have been a fairly smooth transition, if my mother hadn't insisted I was depressed and sent me to a psychiatrist I had nothing to say to. I was actually relieved when my dad left. The tension in the apartment had only been getting worse. Mom was getting more and more dramatic, and Dad was getting more and more silent. He didn't speak to anyone. He would stare at books without ever turning a page, just so he didn't have to interact with any of us. He was miserable. She was miserable. We were all miserable. Dad moving out was more like lancing a boil. He and my mother were suffocating each other, and it had to end. Frankly, I never understood how they made it as long as they did. I never understood how two people who were so extremely different even got married in the first place, but I'm glad they did, for my existence's sake.

I'm not trying to condemn them here. Divorces happen. Toxic relationships break down. It's never pretty. It's never happy. In my opinion, in the case of my parents, it needed to happen in order for everyone to be happy and healthy again. I'm only giving you the backstory so that you understand how I got stuck in this particular situation as a teenager.

Mom insisted I see a psychiatrist, and as I said before, I was not depressed about the divorce; I was relieved. I also didn't have a choice, so I was dropped off once a week or so, to tell the doctor who shall remain nameless here all about why I was depressed and hated my dad. The problem was, I wasn't depressed, and I didn't hate my dad, so I pretty much said nothing. Doctor Moneybags (let's call him that) would ask me questions, and I would say things like, "Yeah," or, "No," or, when I couldn't decide between the two, an I-guess-sinister, "I don't know." I never gave the man any reason to suspect that I was a danger to myself or others. Still, he told my mother that I was, in fact, a danger to myself and others. I denied this tearfully to my mother, when the doctor said I had to be put in a mental hospital so that I didn't murder my family, but he was a doctor, and I was a deranged member of Generation X; branded a smart-ass, a slacker, a punk, a latch-key kid, and every other "X" that the media could invent to slap us across the face with. I had no chance.

Moneybags wanted to put me away that day, but my father put his foot down. It was December, after all. I couldn't miss Christmas! And so it was that the day after Christmas, I was institutionalized.

I met a number of interesting people in the mad house. There was a former child star, who had been on a Saturday morning TV show I had watched years before, whose mental problem was pretty much that she was no longer a child, and her parents didn't understand why. There was another girl who had been put there, because she frequently had sex with her boyfriend and fully intended to continue doing so. There was a boy whose clearest symptoms of insanity included listening to heavy metal music and growing his hair long; another boy whose parents thought he prayed too much; another who had a Mohawk haircut and had smoked some weed. You know ... crazy people.

The point is, despite the opinions of the experts, none of us belonged there.

Dr. Moneybags would come to see me once a week, to continue our non-conversation and collect his check from my dad's insurance. There were other, equally corrupt doctors there who made sure we all took our meds, which were never explained to us. But if we got caught spitting them out, they would watch us swallow them thereafter and check our mouths. If we questioned them or resisted treatment, we were isolated. I once got busted for eating a grape without permission. I was clearly on the path to a depraved life.

While I hadn't been depressed before, that started to change fairly rapidly when I was locked up for months. I didn't see any way out. I started to lose the will to live. I thought if I had to stay there one more night, I would simply die in my sleep. I wasn't about to conform, but I had to pretend that I was in order to survive. The doctors would try to lead me into saying that I wanted to experiment with sex and drugs, but I never took the bait. They were trying to justify keeping me there and draining my dad's insurance money. Curiously enough, when the insurance money ran out, I was declared cured and released.

When I got home, I stopped expressing my feelings so much, for fear of being sent back to the hospital. I lived with that fear every day until I moved out. I learned to hide my feelings and my actions from my parents and others of their generation. I learned to nod my head until the totally-not-insane grown-ups went away, and I just did my teenager thing on my own, letting them think they had won whatever argument they were having with themselves at me. My mom hid all of the knives from me, still convinced I was a danger to myself and others. She even hid my BB gun, which I find hilarious to this day. My dad, unconvinced by the psychiatric conspiracy theories, fantasized about crossing paths with Dr. Moneybags in public and beating the hell out of him. I, too, fantasized about my dad beating the hell out of Dr. Moneybags.

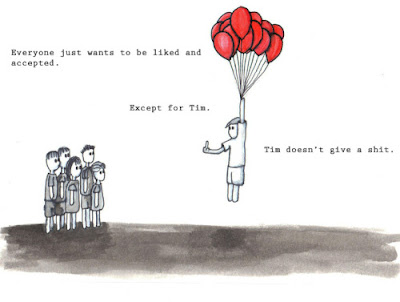

As a result of all this, I grew up to be an obstinate non-conformist. I evolved from actively hiding my actions and feelings to just not advertising them. I would do what I wanted to do, and if someone noticed and didn't like it, I would shrug and do it anyway. If someone, usually from the previous generation, started having a meltdown over my refusal to obey and conform to what they thought I should be doing, I would watch them melt down, for entertainment, or I would shrug and walk away, continuing to do my own thing, not really caring that they were giving themselves an aneurysm over it. It's something I identify as a Gen X trait. I know we're not all like that, but I am, and most of the people I grew up with are, and so many of the articles I read about Gen X support the whole "does not play well with authority figures" stereotype that can be said to define our generation.

So, what does all this have to do with "Dr. Coffee's Pill?"

Everything, as it turns out.

"Dr. Coffee's Pill" was originally an essay assignment in a college English class I was taking in the early 2000s. We'd been studying all of these creative historical figures for weeks, and the professor, Dr. Mary Northcut, whose every class I dutifully signed up for, gave us some prompts to choose from. I chose the one that called for us to imaging some of the people we'd been studying in a support group together. I can't take credit for that part of the idea, but as for who was in the support group, the character of the psychiatrist, the topic of their conversation, and the story that followed, that was all my own.

I based the character of Dr. Coffee on Dr. Moneybags, who had basically stared at me for an hour a week while drinking coffee incessantly, before having me committed. His drinking coffee was the affectation I took the most notice of, so I gave it to my fictional psychiatrist. The artists in the support group were Frederick Chopin, Vincent van Gogh, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Frida Kahlo, all of whom had been affected by profound pain in their lives.

I looked up the artists' own words for a lot of their dialogue, working quotes or stylistically similar phrases into their discussion. The topic of conversation was the relationship between artists and their pain. Would they still be the greats that they were, if someone took away their pain? Dr. Coffee had a pill that promised to do just that.

I dipped into my own pain to write the group session. I went back to my experience with Dr. Moneybags and the mental hospital I should never have been in; the attitude displayed by so many of the Baby Boomers I grew up around, that I should conform, or vanish. Conform, or be erased. Conform, and be erased.

The story was short and to the point. Just the way I like them. Dr. Coffee left the group to discuss his proposition, with the bottle of pills sitting there before them. Would they take the pill and free themselves from the torments of their experience, or would they refuse and continue swimming upstream in a world whose expectations and realities had deeply wounded them.

When the name of the medicine is revealed at the end of the story, it was Basquiat who tied it up so brilliantly, highlighting the truth of the proposed non-solution by crossing out the word. I like to think that, should I find myself in a similar support group for dead artists some day, I would do the same.

My pain is a bottomless well of emotional intelligence. My pain is the ink that I bleed on the page. My pain informs my joy, and thus my joy is boundless.

|

| I stole this screenshot from Austin Kleon, who stole it from the documentary Jean-Michel Basquiat: Radiant Child. |

"Dr. Coffee's Pill" was published to my website as a PDF e-book on December 4, 2004 and in paperback the following year. It was re-issued most recently in 2012, as a Kindle e-book and a print edition available exclusively through my website, via Lulu.com.

Next: "Metrognomes: Worse Than a Gremlin" (2005)